This post is the second in a series inspired by Seth Godin’s Permission Marketing. For the first part, go here.

A rebellion is brewing all around us. You may be a part of it.

Many marketers follow Seth Godin’s permission method, yet the evidence shows a permission revolt against all marketing. Consumers are rejecting Internet marketing that feels intrusive, and we are entering an age of mistrust from a significant slice of the most coveted demographics. Marketers today are following permission rules to the letter, yet they’ve lost sight of the meaning behind these rules. The concomitant rise of interruption entertainment points to what consumers really want to pay attention to. Modern, savvy consumers demand a higher standard for their attention. Marketers can respond by rereading Permission Marketing and using modern tools to renew their commitment to Godin’s rules.

A prospect or customer will not allow a marketer to speak to them unless the message the marketer provides has three characteristics. To build and maintain a relationship, Godin writes, a marketing communication must pass three tests:

A prospect or customer will not allow a marketer to speak to them unless the message the marketer provides has three characteristics. To build and maintain a relationship, Godin writes, a marketing communication must pass three tests:

- It must be anticipated. The recipient is expecting to receive a message and is even looking forward to it.

- It must be personal. The message must speak directly to the receiver, and show respect for their time.

- It must be relevant. The message must address a need or desire of the recipient. It must speak their language.

These characteristics lie at the heart of permission marketing. To first reach a prospective buyer, however, the marketer must use a traditional interruption technique (TV ad, direct mail, banner, etc.) to get the prospect’s attention and ask for permission to build a relationship.

Down The Rabbit Hole

Reading the last sentence, perhaps an objection is forming in your mind. Marketers don’t have to interrupt their customers at all, you think. What about search engine marketing? You are exactly right.

Technology has accelerated since Godin published his book in 1999, leading marketers on an ever-faster chase to reach their markets. Yet in their quest to smooth and perfect the permissive techniques they use, marketers are leaving consumers behind. Some consumers are in open revolt.

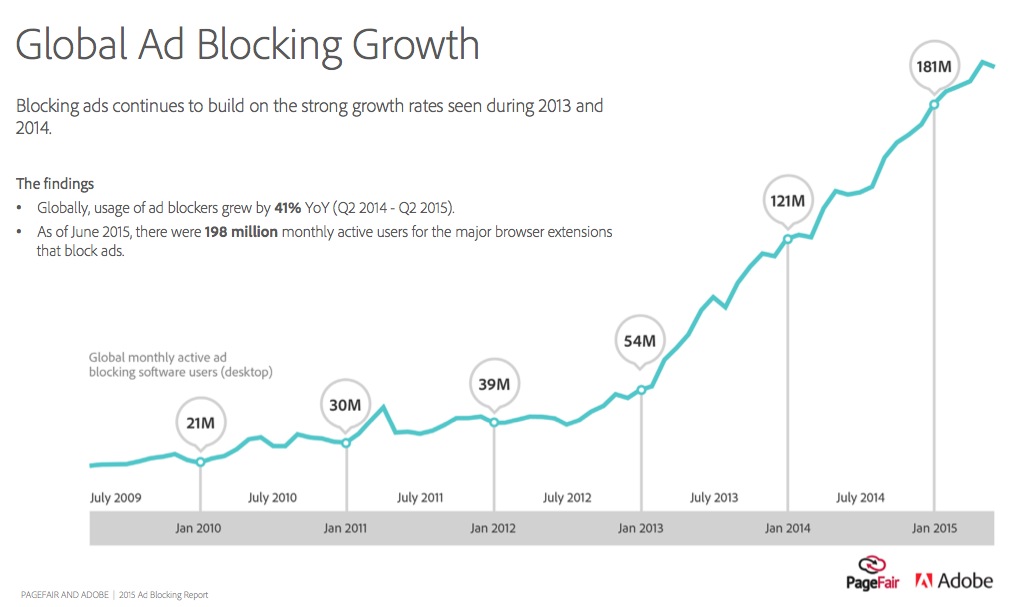

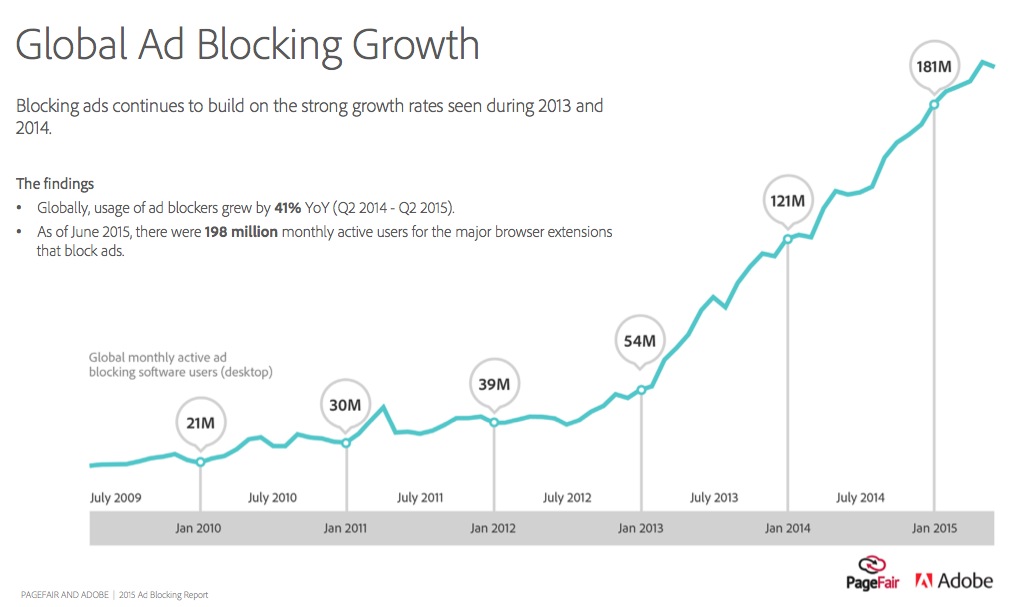

Ad blocking. Consumers are increasingly refusing advertising on the Web, using ad blockers to prevent marketers from reaching them. One study found 15% of US Internet users blocked advertising as of this summer, a share that has doubled in two years[1]. A different report released at the same time showed 10% of US users blocking ads, but also noted that these consumers were younger, wealthier, and spent more time on the Internet than those who did not block ads[2].

When Apple’s recent iOS 9 operating system allowed ad blockers on iPhones, paid ad blocking apps immediately became the most popular downloads on the App Store [3]. The mass refusal to view Web ads is fast picking up steam.

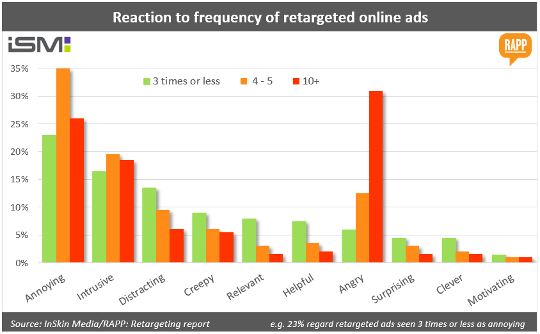

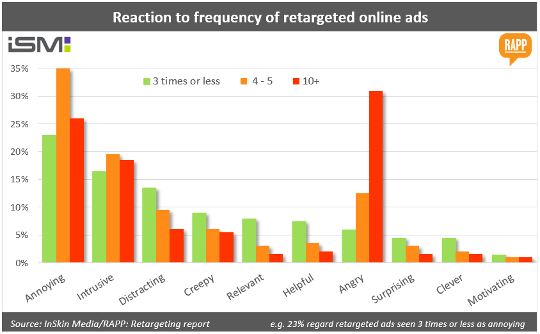

Retargeting unease. Consumers have quickly turned against retargeting, a tactic solely designed to give Web users information they want to make a purchase. A 2013 survey found just 11% of Internet users had negative reactions to retargeting, compared with 30% positive reactions[4]. A year later, a different survey found a range of mostly negative reactions to retargeting, ranging from annoyance to anger, and clear evidence that repeated retargeting discourages future purchases[5].

This promising technique appears to find trouble only months after consumers first become aware of it.

Privacy. Some consumers do not trust the often-anonymous organizations that track their Web activity, and are choosing service providers that promise not to provide personalized marketing. One visible company riding this trend is the anonymous search engine DuckDuckGo, which has seen its search traffic more than double year-over-year while Google’s traffic has reportedly grown at a 10% annual rate[6, 7]. Granted, Google still would not consider this a threat to its search business: DuckDuckGo traffic represents about 0.3% of Google’s volume. Anonymous Web use is an imminent risk to marketers and publishers.

Escape from email. Even email, a favored opt-in channel, may face a reckoning. Thirty percent of email users change email addresses annually. Twenty-one percent of email users will report opted-in email as spam, presumably because it is easier than trying to opt out[8]. A different survey finds that 70% of spam reports are for offers the recipients simply don’t want to receive anymore. Just 40% of consumers say they enjoy getting email from their favorite brands[9]. Email users are overwhelmed and tired of commercial messages.

Marketers have fine-tuned their methods to build detailed dossiers on everyone they speak to. We should be entering a golden age of perfect audience engagement. If marketers can seamlessly provide the information consumers need, consumers ought to be thrilled. Yet the very opposite seems to be occurring. Why?

I Know What You Did Last Summer

Consumers are wary partly for reasons completely outside of marketers’ control. Recent revelations about government data collection have eroded trust in any organization that tracks individuals, certainly in the US. But this is not a full explanation.

Godin intends for permission to mean a customer “raising their hand” to start a relationship with the marketer. This acceptance is explicit and mutual. Yet marketers are often following the letter of Godin’s rules without observing their spirit. Above all, many marketers have forgotten that reaching consumers is a privilege rather than a right. This leads to engagement experiences that can be bothersome, creepy, intrusive, and unwelcome.

- Do you look forward to hearing from brands? You may when it is a few companies that contact you, however most consumers hear from dozens of companies. Often marketers seek permission to begin marketing in subtle ways: you will receive email unless you uncheck a box, or even as a term of use. Technically the marketer received permission so you should expect to receive marketing materials. But you will not welcome them. The effect is multiplied by frequent mailing list rentals. In the end, you are more likely to tune out all marketing rather than pick through the pieces for a few items you really want.

- What do you think when an advertisement has your name on it? In the age of postal mail all letters came addressed to us personally. In the age of the Internet we are more likely to be irritated to see our name in flashing lights and subject lines. We know perfectly well that the message is not individual, it is just tailored by a piece of software that can insert our name (and other details) into the message. Personalization means a card on my birthday – yet even this classic keep-in-touch technique is cheapened by the ease of automation. The Internet has debased the personal so that a veneer of individualization is no longer special.

- Do you think Google knows too much about you? How about the hundreds of corporations that have a profile on you? These dossiers in theory should allow for more relevant product offers and experiences than even before. In practice, they also lead to persistent tactics that become intrusive, such as retargeting that continues after a consumer completes a purchase and makes that consumer less likely to repeat the purchase in the future. Offers can even be too relevant, leading to fear and mistrust. How would you feel being outed by Facebook or learning that your daughter is pregnant from Target?

Think of the Internet as an endless series of blind dates. On a good blind date, you meet your partner at the appointed time (anticipated), your date remembers what you spoke about over email (personal), and you start to build a relationship on things you have in common (relevant). Good permission marketing can feel just as positive.

For many consumers, modern Web marketing feels like a nightmare blind date. He rings the doorbell at a random time, maybe five minutes after you first agreed to meet or maybe five months later. Your date can recall everything about you, but inserts each detail into an obvious shell story that has nothing to do with you. In fact your date knows far more about you than you told him. He shows up with your favorite kind of chocolate, tries to take you to your favorite restaurant and movie, and even offers to pick up your friends on the way. How would you feel about that interaction?

For many consumers, modern Web marketing feels like a nightmare blind date. He rings the doorbell at a random time, maybe five minutes after you first agreed to meet or maybe five months later. Your date can recall everything about you, but inserts each detail into an obvious shell story that has nothing to do with you. In fact your date knows far more about you than you told him. He shows up with your favorite kind of chocolate, tries to take you to your favorite restaurant and movie, and even offers to pick up your friends on the way. How would you feel about that interaction?

You’d flee. After several experiences like it you might reject dating altogether.

The B2B Impact

Business-to-business marketers are just as impacted as are consumer marketers. Even though many B2B companies do a better job of cultivating and educating buyers, they are still prone to send thinly personalized and irrelevant information at the wrong time. What’s more, they are equally harmed if a prospect decides to start ad blocking or to spam-button every commercial message. The permission revolt will not spare B2B even if it comes more slowly.

Market-Us Interruptus

Many marketers are trying very hard to follow Godin’s prescription, and you might argue that the examples of failed anticipation, personalization, and relevance aren’t fair. If these tactics don’t meet the standard, how could anything?

Perhaps existing tactics could receive a better reaction if marketers stop depending on the seamlessness of modern technology, start seeking more explicit permission, and understand that consumer expectations have risen.

As Godin originally conceived it, permission is an explicit opt-in step. The consumer first indicates a willingness to receive marketing messages, usually in exchange for some benefit. Today’s Internet no longer demands this explicit agreement. Instead, marketers often seek permission through terms of service that no one reads, through hard-to-see opt-outs, and through list sharing. Customers may technically agree to these terms, but if they had been asked most would not have granted permission. (A few would, representing the motivated audience permission marketing is designed to build.)

Even more subtle are sitewide terms of use that authorize tracking which consumers implicitly accept the moment they enter a website. Web users no more accept this arrangement than air travelers accept going through security screening. It is presented as an option, but in reality it is mandatory – and thus permission is not granted at all.

Marketers like these tactics because they don’t create an interruption. If consumers are stopped by a pop-up window asking for permission to market to them, won’t most refuse? It’s far better to skip this step and put permission in the background. (The one major advertising channel which avoids both asking for permission and creating an interruption – SEM – unsurprisingly wins the largest share of online ad dollars. But this method cannot in itself build a relationship.)

Yet Godin conceives of interruption as the essential first step to gaining permission from the consumer. Though this step is no longer technically necessary, it is still important. Implicit permission is hardly permission at all. Without an initial interruption, the subsequent marketing will always feel like an interruption to consumers – who will respond accordingly. Marketing from implicit permission can lead to sales but cannot lead to relationships with consumers. When the messaging assumes the relationship, consumers turn away.

Marketers who offer good value in return for the consumer’s attention – and who appreciate the need for anticipation, personalization, and relevance – will still build trusted and profitable relationships. Modern tools do not absolve us of this requirement, and in fact elevate it further. Our personal habits on social networks and mobile phones tell us why.

Angry Birds and Happy Customers

Back in 1999, when Seth Godin first differentiated interruption marketing and permission marketing, an interruption was typically considered a bad thing. Today we don’t perceive it the same way at all, at least if we are interrupting ourselves.

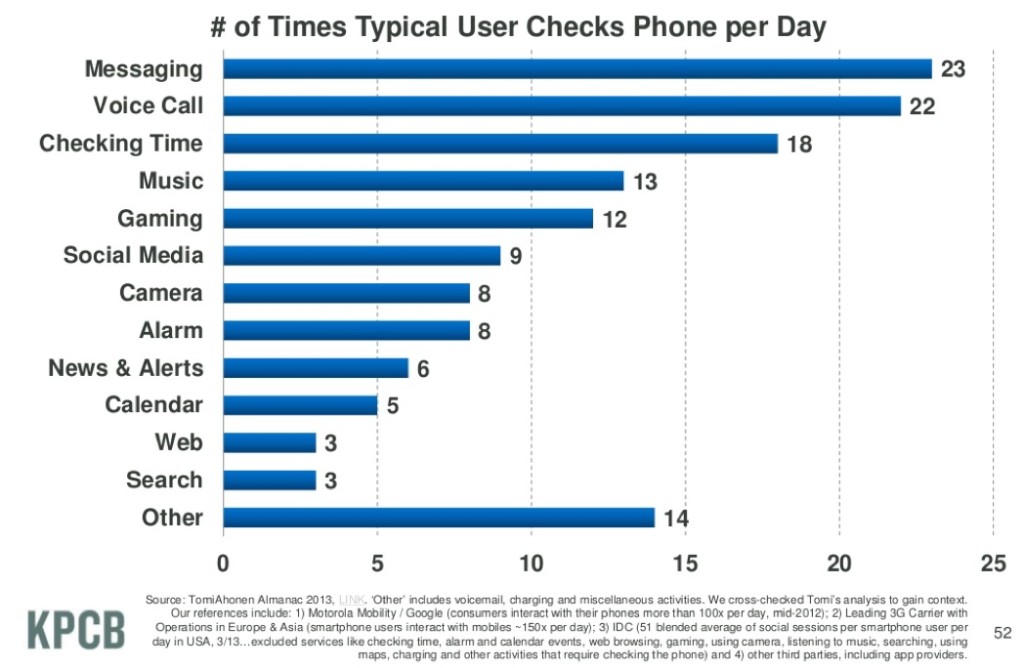

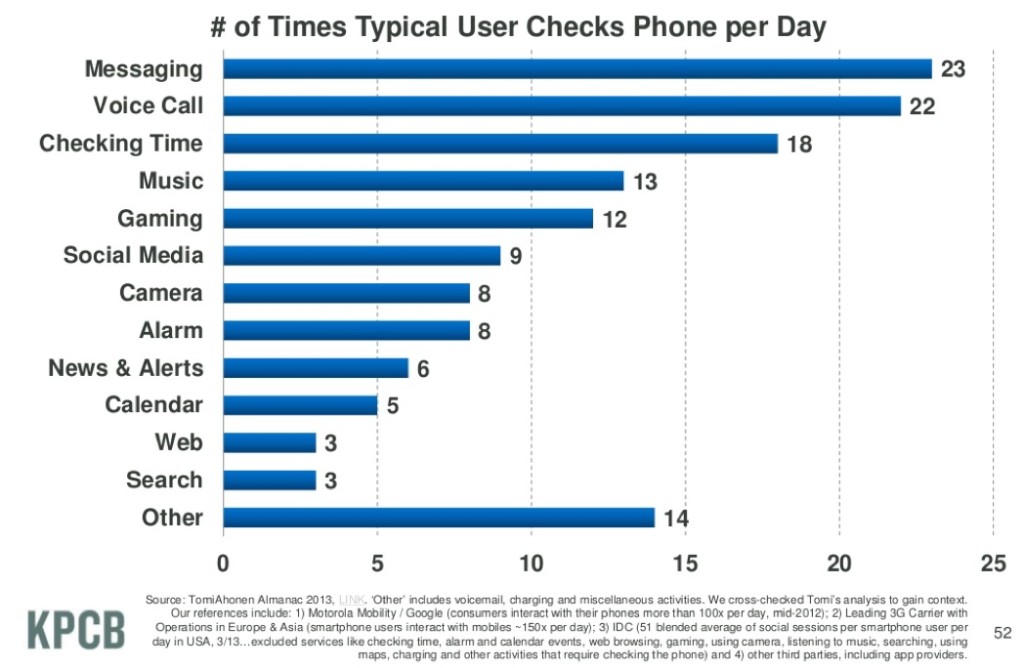

Most consumers are using social media and mobile phones every day of their lives. In 2013, the typical consumer checked their smartphone 144 times a day, an average of once every seven waking minutes. About 50 of those checks were for reasons that could be considered entertainment, such as music, games, photos, and social media[10].

And no doubt our average consumer spent even more time with these distractions on their laptop.

These self-interruptions have become a major source of entertainment in our lifestyle. And it’s no wonder. The services we access so incessantly from our smartphones meet all of Godin’s three rules handily. They are wholly anticipated – desired, craved, even beloved. They are insistently personal, representing communication with our entire circle of acquaintances, or our selection of the one out of millions of apps that is more pertinent to our lives. They are precisely relevant, giving us tweets on up-to-the-second news and real-time photos of our friends. We are willing to distract ourselves – every seven minutes! – because the message is so intensely desirable. Social and mobile has led to interruption as a form of entertainment.

Marketers have shifted ad dollars to Facebook and optimized landing pages for mobile. These obvious reactions to this new world are just just shifts in tactics. Often they don’t recognize the full implications for marketing engagement.

Marketers hesitate to interrupt consumers and the experiences they offer are not as fascinating as interruption entertainment. Couldn’t the permission revolt be quelled if consumers feel that their permission is being respected? And won’t consumers engage if the marketing content is as interesting as an extra life in Angry Birds 2?

Godin gives numerous examples of good permission marketing in his book. They all required an interruption. And notably, some don’t quite meet the criteria of anticipated, personal, and relevant. The frequent flier program he cites doesn’t truly build a personal relationship with the air traveler. A technology company that sends offers for add-ons may be none of these, even though it asks its users to opt in. Columbia Records is lauded for negative option marketing, a tactic that is now discredited by Internet scams.

These examples of permission marketing were great then but would not be so successful now because we have become more demanding. If our glowing rectangle of entertainment can enthrall us so totally, we will only pay attention to a marketer who can do the same. If Angry Birds were reskinned as Coca Cola Crash players would like it just as much. Only many brands have not created anything so compelling.

Marketers today must accept the implications of our interrupted life and adapt their understanding of permission marketing to it. Marketers should have the courage to interrupt us, provided that the information they offer is able to capture our attention as fully as our voluntary interruptions. If they fail to interrupt us, they must accept that no implicit permission will ever take the place of explicit permission, and their efforts to engage with us later will always be treated as unwanted interruptions.

In a future post I will show how some brands are thriving with true permission marketing in a world of interruptions.

ENDNOTES

[1] The 2015 Ad blocking Report | Inside PageFair

[2] comScore and Sourcepoint: the State of Ad Blocking – Sourcepoint

[3] After iOS 9 launches, Ad blockers top the App Store chart | Naked Security

[4] Online Buyers Notice Retargeted Ads – eMarketer

[5] It’s Official: Consumers Are Just Not That Into Retargeted Ads – ExchangeWire.com

[6] https://duckduckgo.com/traffic.html

[7] Google Search Statistics – Internet Live Stats

[8] 15 Email Statistics That Are Shaping The Future: Convince and Convert

[9] Email Statistics

[10] 2013 Internet Trends – Kleiner Perkins Caufield Byers

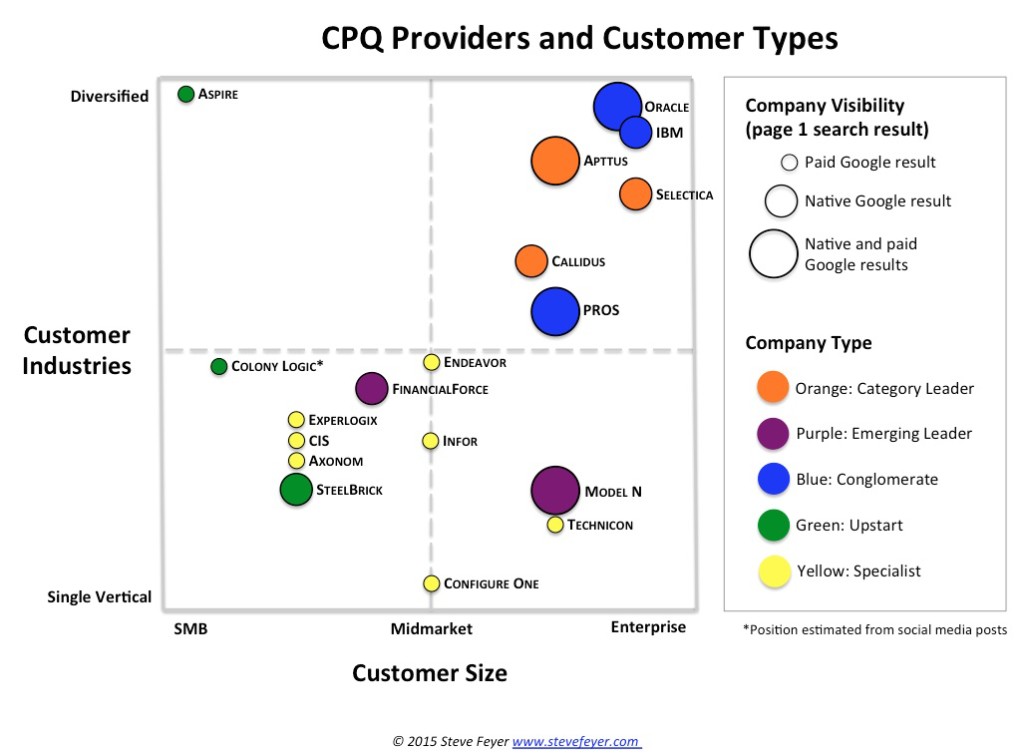

Ries and Trout define the tenets of positioning, the art of influencing how prospective customers perceive a product. As a marketer, you can position your own product, a competitor’s product, or a whole market category. Your successful strategy may include all three elements. The authors use many broadly accessible case studies to show how to position.

Ries and Trout define the tenets of positioning, the art of influencing how prospective customers perceive a product. As a marketer, you can position your own product, a competitor’s product, or a whole market category. Your successful strategy may include all three elements. The authors use many broadly accessible case studies to show how to position.

![]() CC BY 2.0

CC BY 2.0